Visitors are reminded that this website is about education in Victorian times. We will permit matters related the Edwardian period also. Postings that are off-topic will be deleted.

The Real Alice in Wonderland

We are so used to seeing the stylised Alice costume that most people probably think that was the picture that Lewis Carroll had in mind when he wrote his famous books. The blue dress and white apron are iconic, although the modern dress is probably somewhat shorter to that of Victorian times. But few appreciate how diferent our modern take is on the original story, and perhaps many do not know that Alice actually existed and was a real child known to Carroll, and not only that, but it was her insistence that eventually persuaded him to commit the story to print.

Alice: courtesy of

PrincessAlice on Flickr

The real Alice was possibly Alice Liddell, and when Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland was published in 1865 she was thirteen years old. Alice was the daughter of Henry George Liddell who was the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford University, Dean of Christ Church and headmaster of Westminster School. Lewis Carroll, or to give hm his real name, Charles Dodgson, knew him from Christ Church, the College at which he taught, and he became a friend of the family.

On an afternoon in July 1862, Dodgson with another clergy friend, went in a boat on the Thames with Alice and her older sister Lorina and her younger sister Edith. As they rowed a five mile stretch, Charles made up a story to pass the time. It told of a bored little girl who went off in search of adventure. Alice in Wonderland was born. The story was later expanded and embellished before Dodgson, assuming the pen name of Lewis Carroll, committed it to print.

There is some disagreement amongst scholars as to whether Alice in Wonderland was in fact meant to be Alice Liddell. Carroll himself, in later life, said that the story was not based upon a real person. Carroll’s own drawings that acompanied the manuscript did not seem to resemble Alice Liddell, although it has been suggested that they were drawings of the younger sister, Edith. The book, when it went to print was illustrated by John Tenniel, and it is not known who he used as a basis for the drawing, nor whether he was influenced by Carroll.

There are some interesting links to Alice Liddell in the book, however.

Firstly they were set on her birthday (4 May) and half birthday (4 November). In Through the Looking Glass, Alice declares that she is seven and a half years exactly, the same as Liddell on that date. The book is also dedicated to Alice Pleasance Liddell, but by far the most intriguing connection is a poem that appears in Looking Glass which goes like this:

A boat beneath a sunny sky,

Lingering onward dreamily

In an evening of July–

Children three that nestle near,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Pleased a simple tale to hear–

Long has paled that sunny sky:

Echoes fade and memories die.

Autumn frosts have slain July.

Still she haunts me, phantomwise,

Alice moving under skies

Never seen by waking eyes.

Children yet, the tale to hear,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Lovingly shall nestle near.

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

Ever drifting down the stream–

Lingering in the golden gleam–

Life, what is it but a dream?

If you take the first letter on each line all the way through the poem, the name Alice Pleasance Liddell is spelt out.

So what did the real Alice Liddell look like, the girl many people like to think was the real Alice? Fortunately we have a photograph, thanks to Dodgson’s other hobby, photography. In the picture Alice is on the right, with Lorina in the middle and Edith on the right. In the second picture Alice is dressed like a beggar, but it is the first photograph that intrigues me.

Alice Liddell with Sisters

Alice Liddell

Here we have no suggestion of the blue frock and white pinafore of the modern image, nor the long blonde locks, which seem popular from the Disney version. This Alice had short, dark hair, and was dressed much as any other Victorian girls from well to families would have dressed. I don’t suppose it really matters that our modern take on it is not all that accurate, it is more important that the story lives on.

Alice drawing by John Tenniel

There are some people who suggest that the relationship which Dodgson had with Alice was inappropriate, and that his love of photographing young girls was unhealthy. I think those critics miss the point by not understanding the times and the culture. The Victorians may have been our ancestors, but they were also different people to us. They thought differently, acted differently and lived their lives differently. Some of the things they did, we find odd today, but they were just different. For example, they regularly took photographs of dead people, which they propped up with the aid of stands, and these were termed mourning photographs. We would find that kind of photograph distasteful, and perhaps offensive, but the Victorians looked at it differently, maybe because they lived daily with the spectre of death. Similarly, nobody would have even considered that photographing a child was wrong. It was a much more innocent time. Certainly Dodgson liked children, and probably mainly liked girls, but it was almost certainly an entirely innocent pleasure, that sadly has been lost by our modern witchhunting obsession. Even those who have attempted to make something out of nothing have been unable to find any real evidence of inappropriate behaviour and have based their accusations on suggestion and inuendo.

Alice Liddell went on to marry, and lived to the ripe old age of 82, dying in 1934. Lewis Carroll drifted apart from her around the time of the publication of Adventures, probably accelerated accelerated by a political rift between Carroll and her Father, caused by College politics. She went on to have three sons, two of whom died in the first World War.

So it is not clear whether there ever was a real Alice in Wonderland, nor what she really looked like, but in the end, it must come down to how we see her in our mind as we read the book.

Sweet Fanny Adams

A sad Victorian crime is still remembered today when we use the phrase “sweet Fanny Adams” to mean nothing at all, or no result.

Fanny Adams was an eight year old schoolgirl living in Alton Hampshire when the crime took place on 24 August 1867. She went out with her seven year old sister Lizzie, and a school friend, Millie Warner to play in a nearby meadow. On the way they met a young man, Frederick Baker, who offered Lizzie and Millie three-halfpence (1p in modern money) to go and spend in the shops, while Fanny was told she could have a halfpenny if she showed the man the way to a nearby village. She took the money, but refused to go with the man on the two mile journey. He carried the girl into a nearby hop field, and that was the last time she was seen alive.

Later, when the two other girls arrived home, the alarm was raised, and her mother and a neighbour set out to find Fanny. They met Mr Baker in a lane and they asked him if he knew anything. He claimed that he had just given the girls money for sweets, which they accepted, and continued on their way. It should be noted that Mr Baker was a Solicitor’s Clerk so he would be dressed and act in a manner that made him “respectable” and in Victorian times his word would be accepted as truthful.

After two hours of searching, with no result, other neighbours joined in, and they soon discovered poor Fanny’s body in a field. She had been horribly butchered, her head and legs severed, and her eyes gouged out. Her body had also been viscerated, with the otgans scattered around the fields nearby. It took several days to find all the parts, and eventually they were carried back to a nearby doctor’s surgery, of which more later.

The Police set about questioning the suspect Frederick Baker. It was soon found that he had blood on his clothing and two blood stained knives. He was unable to account for these and claimed he was innocent. Questioning witnesses gave circumstantial evidence putting him in the area, but that was nothing that was not already known. More telling was the testimony of a fellow clerk who had been drinking with Baker after work. He claimed that Baker had said that he might have to leave town to which his colleague had replied that if he did he might find it hard getting another job. Baker made a strange reply, “I might go as a butcher.” The final piece of evidence was found two days after the murder, when Baker’s diary was found and in it he had made an entry: 24th August, Saturday — killed a young girl. It was fine and hot.

Baker was tried for murder and although various defences were suggested such as insanity, it took a jury only 15 minutes to return a verdict of guilty. He was hanged on Christmas Eve outside of Winchester Gaol. The remains of Fanny Adams was buried in Alton churchyard.

Two years later, in 1869 rations of tinned mutton were introduced for British sailors. The tinned meat was not popular, and seamen claimed that it was the remains of Fanny Adams. This was perhaps based on the fact that the Royal Navy stores was not far from Alton, and it could be thought that the widely scattered remains of the little girl had found their way into the meat prepared for the sailors. Thus the unpopular mutton was sweet Fanny Adams, which later became sweet FA, and now has rude connotations.

A final twist to the story is that the doctor’s surgery, to which the remains of the girl was taken, later was converted into a pub, Ye Olde Leathern Bottle, and it is claimed that it is haunted by the ghost of Fanny Adams.

The cane and corporal punishment

So far it seems that my post on school discipline Victorian-style has attracted the most views, so I shall say a little bit more about the cane. Most schoolmasters would have used the cane for discipline, and it was not uncommon for senior pupils to use it on junior pupils as well. In fact the cane was used in British schools into the 1970s I believe, although less often in the later years. The cane was usually made of a thin wooden stick probably 10mm thick. Sometimes it was bamboo or rattan, but it was certainly also made out of other wood as well. Birch was used for some canes and it was often kept in a tank so that it was wet and more pliable. The cane often had a curved or crooked handle. The length of the cane was usually less than 1 metre.

Boys were generally caned on their bottom or hands, while girls were often caned on the backs of their legs and also on their hands. It is usually accepted that caning on the hands was probably the more painful. The schoolmaster would choose to cane the hand that was not used for writing, and three or six strokes were given, usually aimed to be placed across the fingers, which hurt more than the palms of the hand. If the hand was withdrawn, extra strokes were given. Caning on the bottom was sometimes aided by the victim bending over a chair, or sometimes over a vaulting horse, but it was also possible that the pupil would just be told to bend over and touch his toes. A number of strokes were applied, sometimes only one or two, with six of the best being reserved for serious offences. It was not common for the cane to be given on the bare bottom, it was usually given over clothes, but in boarding schools it would often be given at the end of the day when the pupil was wearing pyjamas.

That said, at Eton, during Victorian times, a recalcitrant pupil might be given the birch. This was not a birch rod, but a cluster of thin birch branches, bound together, and looking much like the head of a besom (the broom used for sweeping leaves). In this case the pupil dropped trousers and underpants and was hit repeatedly with the birch. This inflicted a mild pain at the first stroke, which built into a more intense pain with each subsequent stroke. The birching was usually given in a kneeling position and never over clothes. The school punishment was reinforced by home punishment and the wise pupil would not willingly admit to a caning at school as this might well elicit a further punishment at home.

The Victorian child soon learnt that if he wanted to misbehave he should ensure that he did not get caught. Did the punishment work? There is little doubt that for some pupils the threat of a caning was a sufficient deterrent to prevent misdemeanours. For the more serial offender it did not completely stop bad behaviour, but it certainly curbed it. Was it abused? Almost certainly. There is little doubt that there were teachers and prefects who gave punishments in an unfair or sadistic way. Corporal punishment finally ended in Britain in the late 1980s and one wonders if the loutish behaviour of some teenagers today would not have been tamed by application of some old-fashioned punishment. When I was a boy, rules were black and white, and you knew how far you could go. Nowadays it appears that rules are meant to be broken and you get away with as much as you can. A bit of Victorian discipline would perhaps not come amiss, or do you have better ideas on how to tame young people today?

Discipline Victorian Style

One of the things that fascinates modern children who visit our Victorian School is the discipline. It seems to me that modern pupils have little or no concept of the ways in which children were disciplined in years gone by.

The first thing to say is that discipline was very strict. In some ways it had to be, because school classes were often large, and were led by one teacher with assistance from monitors or pupil teachers. But also there was a belief that children had to be trained to do good.

The first thing to say is that discipline was very strict. In some ways it had to be, because school classes were often large, and were led by one teacher with assistance from monitors or pupil teachers. But also there was a belief that children had to be trained to do good.

Some of these beliefs came from religious views. Christian teaching said that people were born with a tendency to do wrong and therefore needed training to do right. We are all familiar with proverbs such as “spare the rod or spoil the child”, and “train up a child in the way he should go: and when he is old, he will not depart from it.” The Victorians fully embraced this thinking and believed that it was essential that children be taught to keep to the rules.

This is quite different from modern thinking, where children are taught to question everything they are taught, and quickly learn how to push at the limits. In addition, parental discipline has declined, and schools have had to follow the pattern.

In modern schools a cane is considered almost barbaric and any form of physical punishment is termed abuse. The Victorians had no such scruples and used canes, the slipper, the ruler and even the belt, to discipline wayward children. Undoubtedly there was some abuse, those who used the punishment excessively, but there were also many who exercised their authority fairly and with restraint.

Interestingly enough, many modern children seem to think they might prefer some form of mild corporal punishment to the sloppy and ineffective punishments meted out in schools today. I have heard of school classes that have descended into chaos because teachers have been unable to maintain control, with their only weapon being the detention. I have wondered, for many years, whether a detention has done any good. I have never spoken to anyone who has said to me, I really appreciated those detentions, they got me back on the right path, but I have had several who have said to me that corporal punishment kept them on the straight and narrow.

You may have gathered by now that I am in favour of corporal punishment, as long as it is carried out fairly. My belief is that a short sharp shock is often sufficient correction to point a child in the right direction, and it is quickly over. Often the possibility of punishment is sufficient deterrent in itself. In my view, the detention is a feeble punishment that achieves very little and results in a fair number of naughty children growing up into uncontrollable teenagers and anti-social adults.

I’ll come back to the subject later.

Visiting schools with the Victorian experience

Although I volunteer as a Victorian Headmaster in a real Victorian School, I have been aware for some time that it is not always possible for schools to visit us. Undoubtedly there is a lot of work involved in organising a coach outing, and some schools are too far away or just don’t have the resources to come to us. For a while I have been wondering whether I should go out to schools and provide some sort of Victorian Day.

If I were to do that, I would have to acquire a number of props that could be transported. I wonder how I could carry a full size blackboard and easel, for example. Unfortunately it is impossible to find a stick of chalk in most modern schools, let alone that vital bit of school teachers equipment, the blackboard. Some of the other things are easier, slates, books and a selection of Victorian artefacts. I would probably also need clothes, since dressing up is a vital part of the Victorian experience. I have a genuine gown, mortar board and cane as part of my outfit, and I try to wear other clothes which are not too incongruous. One of my predecessors had a Victorian frock coat made up, which must have been splendid, and which I envy, but I have not managed to raise the necessary finance for that yet, and nothing has come up on Ebay in my size!

I wonder how many schools would want me anyway? It would have to fit in with my other work: I am a self employed publisher, so I can usually move things around to accommodate my Victorian School work, so it is not too much of a problem. I think I might try to dip a toe in the water and see what happens. In the meantime if anyone reading this wants a visit then they can contact me at admin@victorianschool.co.uk. I suppose I ought just to say that I live near Minehead in the South West of England.

Another school visit

Had another visit to our Victorian School today, the second this year. I always find that the first two or three visits of the season are a little challenging, as it takes me time to get into the character of a Victorian headmaster. After two or three times I seem to be able to perform more easily.

It makes a great deal of difference which school visits, because some groups are easier than others. We generally take children at KS1 and KS2, which for the benefit of the uninitiated ranges from 5 years old up to 11 years. Some of our volunteers prefer working with younger children and some prefer the older ones. Personally I like working with a variety of ages, because each group has something to offer. The school today was mainly children of ten or eleven, and they managed to ask some quite inquisitive questions, which meant that they were thinking about what we were teaching them. There are certain questions which crop up regularly, of course and the technique is to make sure you don’t sound bored when you answer.

The Victorian school life is so far removed from that of a modern school pupil, that it is difficult to grasp how hard it must have been. Some Victorian teachers were cruel and harsh to their pupils and discipline could be hard. Learning was more repetitious and rather boring, yet most children did gain from their school the knowledge that their teachers attempted to impart. In our area, I wonder how much education benefited the pupils, since most would have gone on to menial labour work in agriculture, but perhaps there were some who went on to more demanding jobs, and undoubtedly those able to read and write would have used those skills even in a rural setting.

Of course in a short visit, which usually lasts no longer than three or four hours, it is impossible to do more than dip into things of the past, and all one can really hope for is to awaken an interest in history, and in our case Victorian history. Just now and again a school pupil visits the museum again with their parents.

A sample of Victorian School life

In a recent conversation, I was discussing how many traditional skills have been lost over the years. Even in my own lifetime I can think of skills that have declined if not actually disappeared. Things like woodwork, cooking and knitting are no longer everyday skills, and many of the everyday talents of a Victorian Schoolchild would just astound the modern child. Take for example, handwriting. Many modern children can’t write legibly, can’t spell, and make elementary grammatical mistakes. You don’t need to look hard to find words like tomato’s, do’nt, could of done, and even grammer. But even more, the beautiful copperplate handwriting of Victorian and Edwardian times has been replaced with an illegible scrawl. No doubt part of the reason is that computers are a component of everyday life, and spell and grammar checkers take away the need to learn, but the real issue is that children are not taught these basic skills in school.

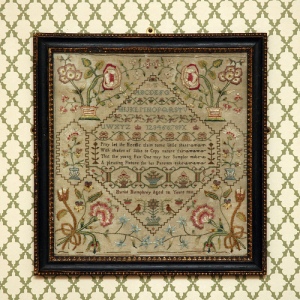

Sampler from Strangers’ Hall, Norwich, Norfolk, England

I am sure I will take up the subject of writing skills in future posts, but what I really want to mention here is the Victorian sampler. For those who are not informed, a sampler is a piece of needlework, so called because it demonstrates the stitching skills of the creator. It was not uncommon for samplers to include pictures and text, and these are highly sought after and valuable. As a typical male, I can’t tackle more than basic sewing, but then neither would Victorian boys or men. The Victorian lady, would be another story, because from an early age they would have been taught to sew, and by the age of ten or eleven they would produce a sampler of a quality that would defeat most modern needlewomen. Actually I have never seen a modern sampler, I wonder if anyone still makes them, I would be interested to know. But the Victorian sampler is an amazing demonstration of needle skills and dexterity.

I suppose that in the modern world there is no need to produce a sampler, but what a proud achievement it must have been for the Victorian child. I can’t help but regret its passing.

SATS tests and the Victorian Headmaster

The current disturbances and protests about SATS tests raise many issues and concerns. Do we test our children too much? Should the school curriculum just be based on academic skills or is it as important to teach other skills as well?

The Victorian school child was certainly tested and the results were every bit as important as SATS tests are today. On the other hand, there was a recognition that scholastic achievements alone were not the total of all that school life was about. The Victorians placed a great deal of emphasis on moral teaching in the classroom, and children were brought up with a very black and white view of right and wrong. Perhaps the teaching was too intense and too monotone, but at least there was guidance. Unfortunately many of the young people leaving schools today have a very confused view of right and wrong. Whether they are brighter is open to argument.

A Victorian Headmaster

When I was young I always wanted to be a teacher. I never dreamed I would make it to become a headmaster. I am a Victorian headmaster. And I am not over 100 years old! Well maybe I feel over 100 years old sometimes, but that’s another story. No, I am a volunteer headmaster at a Victorian School. And great fun it is. In the next few posts I’ll tell you some more, and also make some comments on schooling and education as well.